A Suggested Three Year Curriculum

for Adult Sunday School

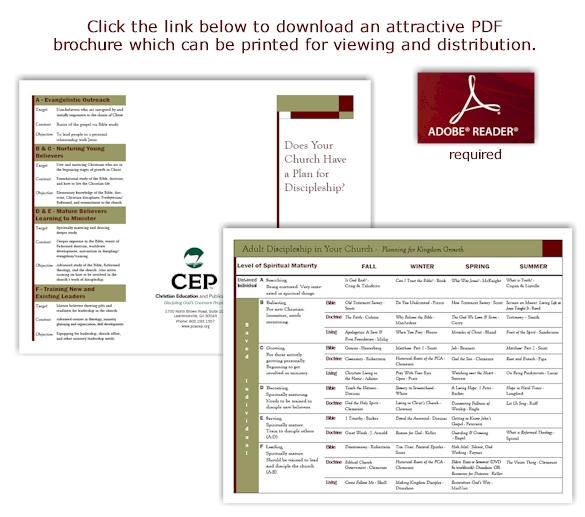

CEP has developed a suggested three year curriculum for your adult Sunday school or other discipleship group instruction setting. The curriculum recommends book studies which cover Bible, Doctrine and Christian Living. The curriculum chart further breaks down the recommendations based on the level of spiritual maturity of the participants as indicated below.

| Level of Spiritual Maturity | |

| A – Evangelistic Outreach | |

| Target | Non-believers who are intrigued by and initially responsive to the claims of Christ. |

| Content | Basics of the gospel via Bible study. |

| Objective | To lead people to a personal relationship with Jesus. |

| B & C – Nurturing Young Believers | |

| Target | New and maturing Christians who are in the beginning stages of growth in Christ. |

| Content | Foundational study of the Bible, doctrine, and how to live the Christian life. |

| Objective | Elementary knowledge of the Bible, doctrine, Christian disciplines, Presbyterian/Reformed, and commitment to the church. |

| D & E – Mature Believers Learning to Minister | |

| Target | Spiritually maturing and desiring deeper study. |

| Content | Deeper exposure to the Bible, tenets of Reformed doctrine, worldview development, instruction in discipling/ evangelism/training. |

| Objective | Advanced study of the Bible, Reformed theology, and the church. Also active training on how to be involved in the church’s work of discipleship. |

| F – Training New and Existing Leaders | |

| Target | Mature believers showing gifts and readiness for leadership in the church. |

| Content | Advanced courses in theology, ministry planning and organization, skill development. |

| Objective |

Equipping for leadership, church office, and other ministry leadership needs. |

All included resources can be provided for you and your congregation by the CEP Bookstore. For further assistance in choosing a particular book-study or to place an order, contact the CEP Bookstore at 800.283.1357 or visit our website, www.cepbookstore.comHint: Use the “Search” box and type all or a portion of the book title